Limited upside, but significant downside

Today’s bond investors have a tough task. Faced with low interest rates and bond yields, the temptation is to bias bond portfolios to be: 1) underweight duration in fear of higher interest rates ahead, and 2) overweight credit risk in order to make up for an income requirement or in pursuit of better total returns.

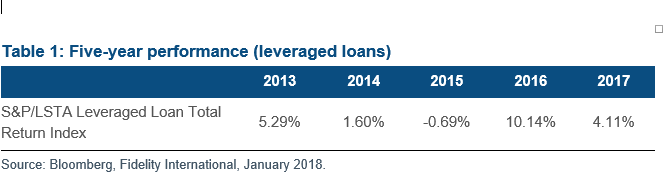

Such ‘short duration credit’ positions range from short duration high yield and leveraged loans, to asset backed or private debt with floating rate structures. For asset allocators, these strategies offer the allure of attractive yields and most importantly, low volatility.

Yet, often, an inherent assumption in the attraction of these asset classes is that volatility is an appropriate measure of risk. Unfortunately, this is not always the case.

Volatility, as a statistical concept, tries to fit the history (or expectations) of returns into what is known as a normal distribution. Normally distributed returns apply equal odds to extreme losses and extreme gains. Yet the problem for a bond investor is that extreme gains are impossible (you are limited by getting only your coupons and par back), while extreme losses are not (you could lose all your capital if a company defaults). Put another way, upside is limited but downside can be significant.

A simple way to illustrate this is to show how a normal distribution underestimates the frequency of extreme negative outcomes. Using 10 years of monthly data, the chart below compares the distribution of monthly returns for US leveraged loans against what a normal distribution implies based on a volatility estimate. While infrequent, significant drawdowns can happen - historically, monthly losses of greater than 5% have been a 2.5% chance occurrence, happening every 3.3 years on average. Yet a normal distribution puts those odds at 0.5%, or once every 16.7 years.

Looking ahead, it’s difficult to identify the catalyst for the next downturn but it is conceivable that challenging liquidity conditions in credit markets will give rise to significant tail events. A volatility measure most certainly will underestimate the chances of that happening.

Source: Fidelity International, Bloomberg, S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan Total Return Index, based on 10 years of monthly total returns to 31 December 2017.

Leveraged loans

Leveraged loansPast performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

Choice of data can hamper results

Another problem with volatility is that the choice of historic data used for its calculation can have a significant impact on the result. In statistical terms, this means the variance of returns is not constant over time.

Source: Fidelity International, Bloomberg, Barclays US High Yield Index, based on monthly total returns to 31 December 2017.

Table 2: Five-year performance (US corporate high yield)

Table 2: Five-year performance (US corporate high yield)Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

Over coming years, the volatile returns experienced through the financial crisis will fall out of standard estimates using 10 years of data. This will lead to a significant fall in commonly cited gauges of risk.

The chart below simulates this effect for the high yield asset class. Assuming that the variance of returns post-financial crisis stays the same post-crisis, the impact on a volatility estimate is significant, falling from 10.6% in December 2017 to 6.0% within 2 years. As the returns experienced around the height of the financial crisis wash out of the calculation, ‘risk’ - as measured by volatility - almost halves.

Investors should consider a wider array of risk approaches

To summarise, the financial crisis of 08/09 provided a stark reminder of the limitations of volatility as a risk measure, particularly in credit. Back then, investors were attracted to floating rate and supposedly high credit quality securities that demonstrated low marked-to-market volatility. Sounds familiar?

No doubt the underlying sources of risk will be different this cycle, but the lessons equally apply today. Whether it is the unrepresentative history used for calculations or simply neglect of the tail risk that credit can exhibit, investors who look beyond volatility measures and consider a wider variety of subjective and objective risk approaches should be better prepared for uncertain times ahead.

In follow-up article, we will look at what risk measures are best to use for credit investing, combining both objective and subjective approaches.